Total mileage on Day 10: 5

Beginning altitude (Lobuche): 14,272 ft

Final altitude (Everest Base Camp!): 17,700 ft

————————————————————

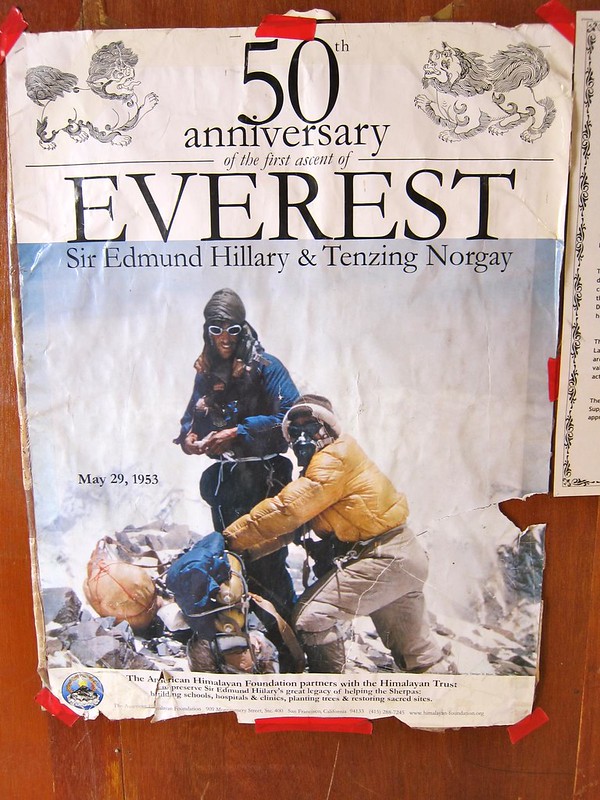

After 10 days of cold nights and exhaustive hiking, today we would finally set foot on historic Everest Base Camp. Although we wouldn’t be hiking to the top of Mt. Everest, today was our own “summit day” in a way, and we both sensed that this day was about much more than reaching EBC.

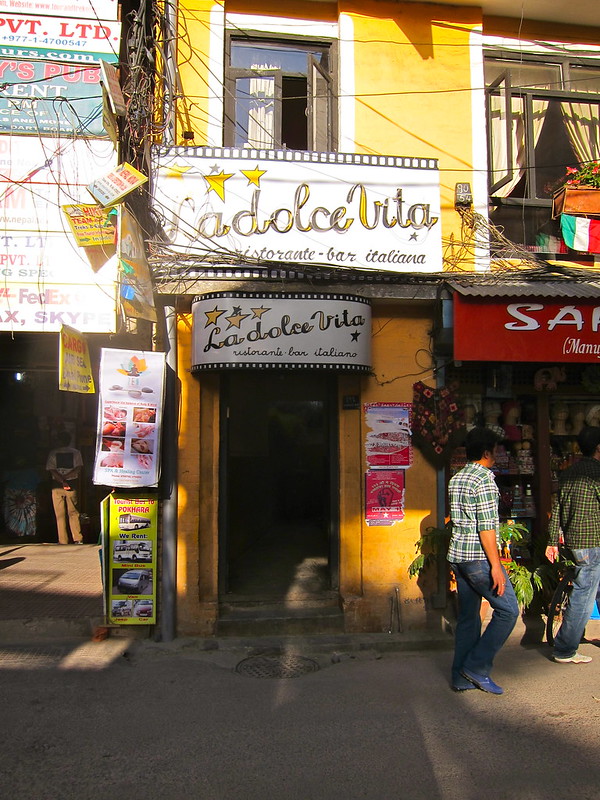

With less than a week before our flight back to the US, today would mark the final adventure of our 8-month journey that had taken us to 9 new countries and enamored us with experiences we would treasure and covet long after we had left. Since leaving home, we had been in a constant state of change, regularly shuffling by foot, bus, scooter, train, sometimes plane, and only stopping briefly to take in the sights, foods, and conversations of one place before stuffing our backpacks and moving on to yet another. Change, in a way, became the only thing that stayed the same, and yet, that in itself was finally about to change too. We knew that once we reached Everest, we would have to turn our backs on EBC–on this entire trip–and literally begin walking towards home.

———

We set out from Lobuche early, around 7 in the morning, with a lighter pack than usual. Last night we had reorganized all of our belongings so that we had the essential gear that we would need for only one night in just one backpack. We left my pack (with nonessential items) in the storage room of our hotel in Lobuche and carried in a single bag: 2 sleeping bags, 1 flashlight, toothbrushes, shard of bar soap for washing hands, scarf for drying face/hands after washing, toilet paper, and altitude meds, but no books or clothing except what we were already wearing. (The frigid temperatures had already made changing clothes impossible, anyway.) Not only would this lighten our overall load, but this would also allow me (still battling a sinus infection) to hike without a pack and thus increase the chances I would reach EBC without needing altitude meds.

Our plan for the day was to:

- Trek to Gorek Shep, the last village before EBC

- Reserve a room for one night in Gorak Shep and drop our remaining bag

- Trek to Everest Base Camp and explore for a couple of hours

- Return to Gorek Shep before dark to sleep and then begin our descent in the morning

The trek out of Lobuche reminded us of the surface of the moon; there were no trees, due to the lack of oxygen, and the frozen terrain was grayish brown, with scattered boulders that had once rolled down from the peaks that surrounded us. We walked slowly to avoid over-exertion and headaches and took in the stunning topography.

[Looking back at Lobuche.]

[Me leaving Lobuche, and a dog we hoped wouldn’t follow for too long.]

[Scott, packed light, with all of our gear]

[“Moonscape”]

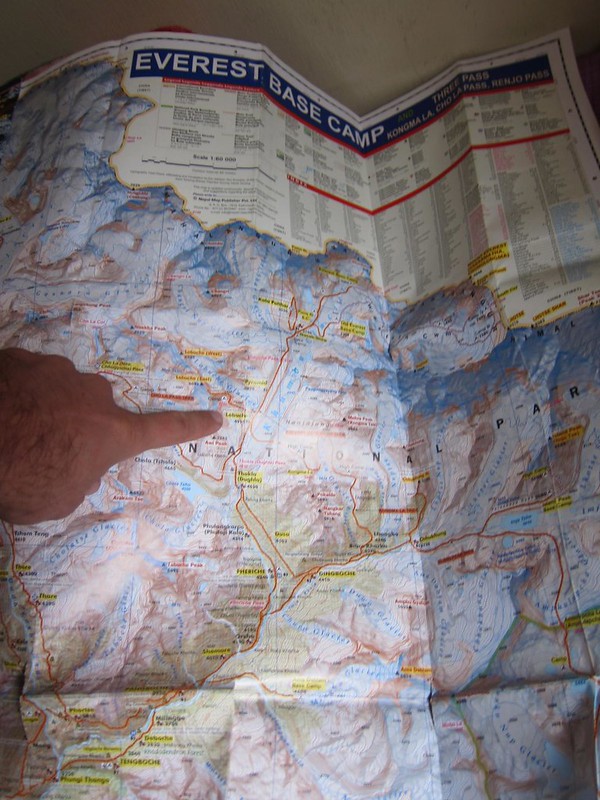

After about an hour, the landscape began to change dramatically. To our right, there was a valley in which the ground was nothing more than crumbled piles of rocky spires and blocks, where brown dust mixed with dusty gray boulders of ice. Looking at our map, we quickly realized were looking at the Khumbu Glacier, the highest glacier in the world.

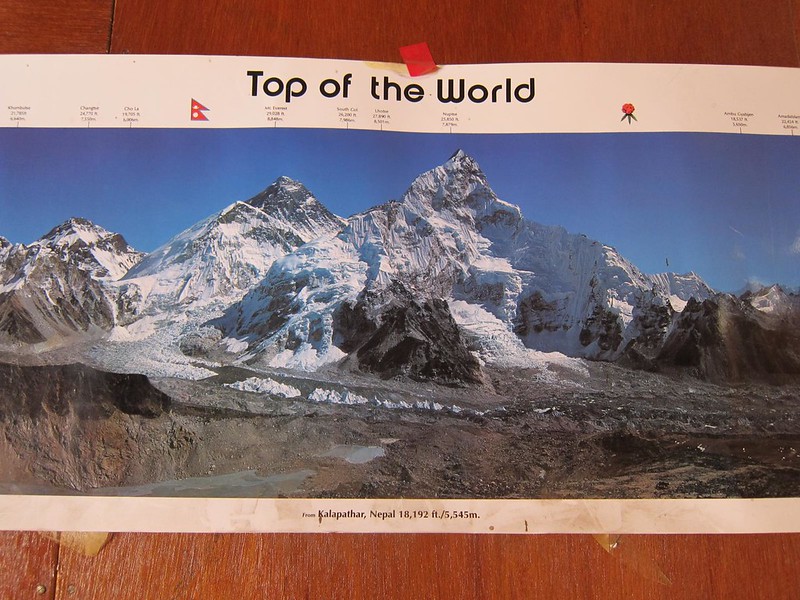

The Khumbu Glacier is an enormous frozen river that begins halfway up Mt. Everest, crashes down the face between Everest and neighboring mountains Nuptse and Lhotse, and runs parallel to the final part of the EBC trail between Gorek Shep and Base Camp.

The glacier is constantly changing, reshaping, popping, and sliding. As a whole, it is said to move about 120 feet per year, though the top portion just above Base Camp, known as the Khumbu Icefall, moves much faster– about 3 feet per day!

[Khumbu Glacier]

[The always-moving Khumbu Glacier]

[Celebrating prematurely]

The trail was eerily empty, save for the occasional yak train or Sherpa with supplies headed for Gorak Shep. Although still well-defined, the trail was noticeably more rocky and slippery than it had been over the past week, and we had to noticeably more careful not to slip and land on a jagged rock or stream.

About 2 hours after leaving Lobuche, Gorak Shep appeared in the distance as we climbed over a tall ridge.

[Entering Gorak Shep. The village’s red- and blue-roofed lodges at left, and the Khumbu Glacier at right, leading to Everest (the shoulder of Everest is visible on the far right)]

[Gorak Shep]

Gorak Shep is a makeshift hiker’s village, open only during the Everest summitting seasons (late spring and early fall), with no permanent residents due to the cold and lack of supplies. The town is notorious for being terribly cold and unpleasant for sleeping, due to the lack of breathable air. (One guide described Gorak Shep to us as a “s***hole”. We did not find it nearly that unpleasant.)

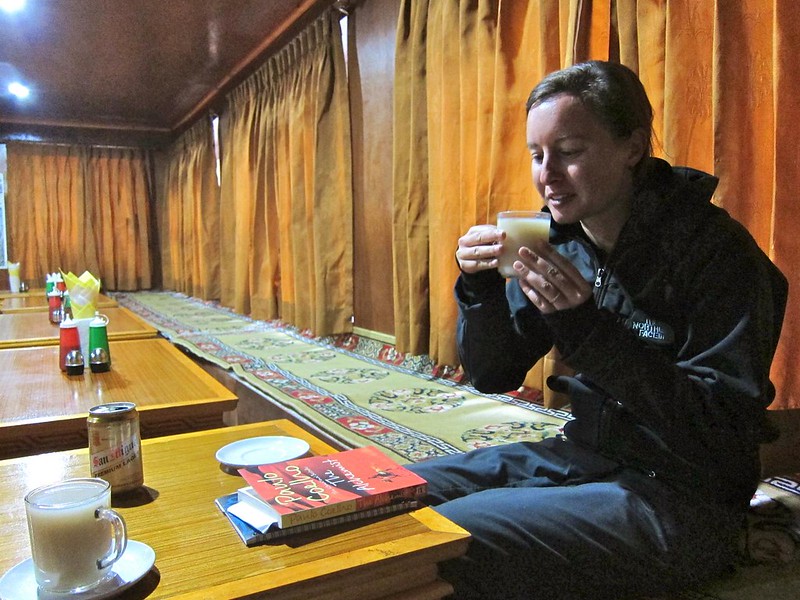

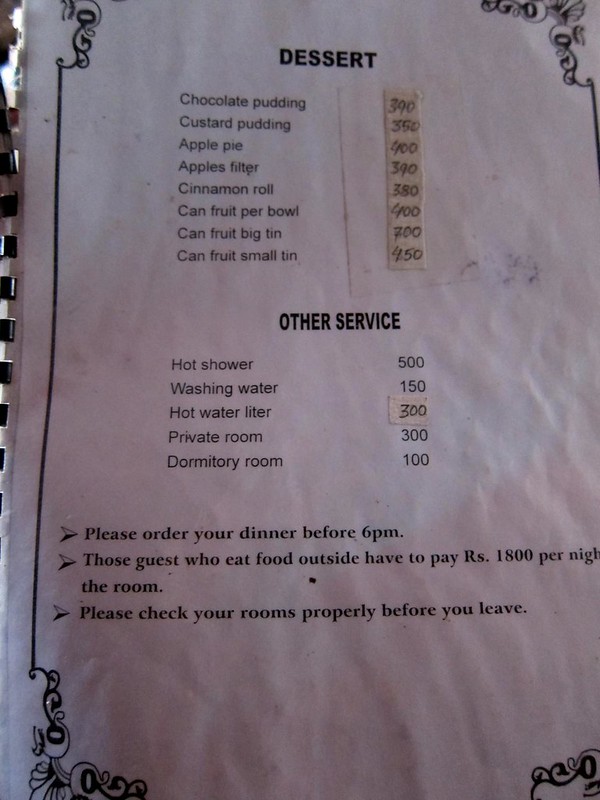

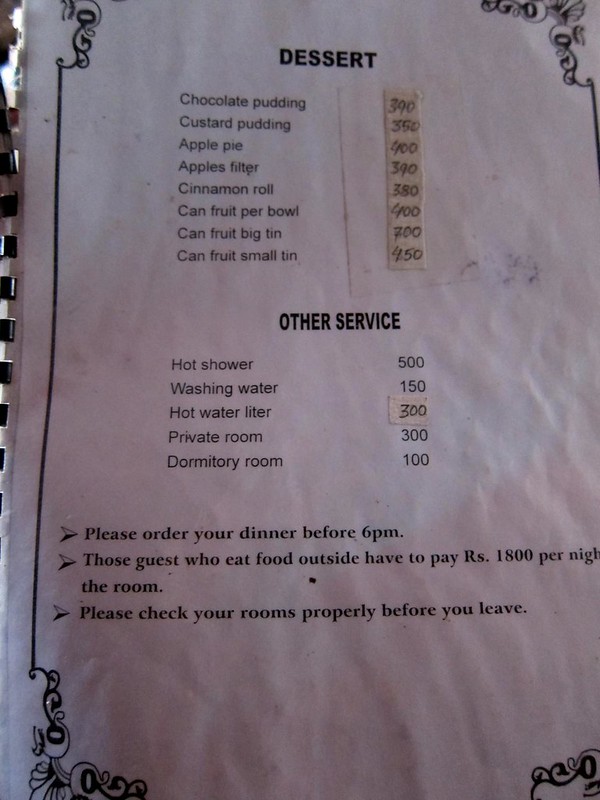

Once at Gorak Shep, we reserved a room at the first lodge we found (we were worried about not being able to get a room, due to all of the hiking groups), tossed our belongings into it, and went to the hotel’s main lodge, where we refueled on a midmorning European-style cinnamon roll, milk tea, and hot Nepali soup.

[Below, the menu at the hotel lodge. Food prices had gone up substantially (although ludicrous for Nepal, $4 for a piece of hot thick apple pie is nothing after you’ve just spent your last reserves climbing to the base of Mt. Everest), and hot showers were now $5 a pop. Luckily, it was too cold to shower, and our room still only cost $3…….. we couldn’t complain.]

We were ready to make our push for Base Camp at last.

[Trail alongside the Khumbu Glacier, between Gorak Shep and Base Camp]

I suppose I can best describe this last leg of our ascent as introspective. The air was eerily still, and our labored breathing was the only sign of life in this rather desolate but beautiful place.

[A sweeping view of Nuptse and Everest, the Khumbu glacier, and the trail leading into EBC. Scott’s audible breathing is a reminder of how hard breathing had become. This is how we sounded for about 2 days.]

There’s no exact moment when the peak of Mt. Everest suddenly becomes clear, as if to mark your arrival more officially than where you were a few steps before. For most of our afternoon walk, its peak hovered in our peripheral vision, still another 12,000 feet higher than us, but close enough to see some of the details at the top.

[The peak on the far left is one shoulder of Everest. The summit can be seen a little farther to the right, with clouds nearly obscuring its peak.]

The gravity of knowing where we really were grew heavier the closer we got, and it didn’t take long for sentimental emotions of reaching EBC, of being in this place, of realizing our trip would soon be ending, to come crashing to the forefront of our thoughts.

Noticing that a storm would soon cover its peak, we stopped to take a quick picture of us with Mt. Everest, fashioning our camera to a rock with our mini tripod. With the clouds moving in, this would be the last time we’d see its summit on our trek.

[Us with Everest’s peak behind us (left-center, mostly covered by clouds)]

Soon, we could see a tiny yellow tent-village in the distance. We soon realized that we were finally looking at Everest Base Camp. [The now well-defined Khumbu Glacier is on the right.]

With EBC in our view, we walked for what must have been at least 45 more minutes along the edge of a mountain. As we got close, we swung down and to the right over a “bridge” made of ice and crumbled glacier rock, with a drop off into the icy pool below to our left.

At long last, we had arrived at EBC! Rather than scrambling to look around at the sights (the summit teams! the colorful flags! Mt. Everest!!), we turned to each other and simply reveled in a long sappy embrace. We’d not only accomplished something that a few days ago we thought might be impossible, but we also knew this was the beginning of the end of something much greater than this trek.

We had made a sign the night before out of a blue handsewn bag I had been given in India when I bought my shalwar kameez in Jaisalmer…

[The last picture of our worn, beloved (and very necessary!) map, marking our arrival at Everest Base Camp… only a couple of miles from the Tibetan border (in beige)]

As a surprise to me, Scott had been carrying a tiny bottle of “Everest” whiskey to celebrate (essential items only…!).

A couple of guys from Europe asked to borrow our sign for a picture (I think they held up the other side, on which we had written “Hi Mom and Dad”…:))

Although many trekkers were being encouraged by their guides to turn around here, at the official “picture spot” of EBC, we had the freedom to walk into EBC and explore for as long as we wanted because we were on our own (as long as our lungs and the impending sunset would allow).

As we began the walk into the graveled, rocky trail that led through EBC, we noticed that we weren’t quite on solid ground. Every year, EBC is built upon the glacier that we were now walking on; therefore, every year EBC is set up a little differently to account for the shifting landscape. Although the ground felt solid, we were keenly aware of the groaning and shifting of the land and splashing of fallen rocks into the pools around us as the snow melted. Boulders were perched precariously on blocks of ice, as if they had been placed there by some other power. In a place with so little native life, EBC itself appeared alive!

EBC was set up as one long trail that ran from the “photo spot” to the Khumbu Icefall, the true beginning of the trail to the summit. Hundreds of yellow tents lined the path, and flags declaring the summiting teams’ nationalities were prominently displayed. Summiters and their Nepali guides sat around in the their tents or in small groups chatting. Medical tents sat off to the sides, and make-shift mess-hall tents were erected within each summiting group’s camp. I couldn’t believe that after years of wondering what it would “feel” like to be at the base of Mt. Everest (would there be roads? what would the people look like?), I was finally here, and I was surrounded by people who would soon attempt to climb to its summit.

[Tents leading up to the Khumbu Icefall.]

After walking about half a mile through the maze of tents, we saw a large beige tent with a sign that read “Glacier Works– Rivers of Ice: Vanishing Glaciers of the Greater Himalaya.” We had read about this exhibit before we had even arrived in Nepal; it was a photo exhibit that was on display simultaneously at both MIT in Boston and at Everest Base Camp in Nepal (we must have been destined to see this exhibit) to bring attention to the dramatic glacial melt that has been occurring in the Himalayas over the past 30 years.

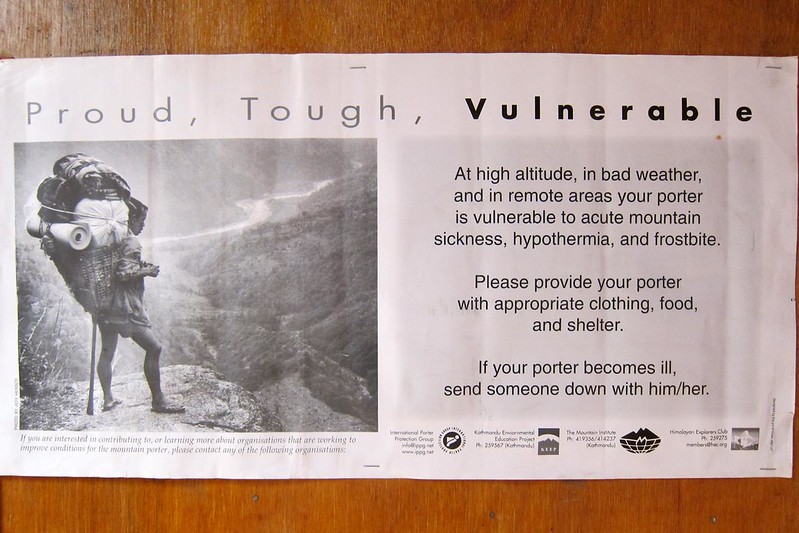

We stepped inside and were greeted warmly by an older blue-eyed American man named David, who walked us through the exhibit, picture by picture. He had taken the majority of the pictures himself over his 32-year climbing career, taking us out of the tent occasionally to point out the various mountains and melting glaciers in their real form. With the way he talked about the disappearance of the Khumbu Icefall and other important glaciers in the region, it was clear that this was his passion. Some of his stunning before and after photos can be found at the following site: http://www.glacierworks.org/

Just as the three of us were standing outside together, a frightening rumble and crash drew our attention to a nearby mountain to our right; although we couldn’t see it, David explained that it was “simply” an avalanche (“They happen several times a day,” he explained.). As the glaciers were melting and becoming more unstable, these avalanches were apparently much more common than they have been in years past, and they were making the accent up Mt. Everest much more dangerous. Hikers were being forced to hike over the Khumbu Icefall in the middle of the night before the sun rose, when the ice is most stable and less likely to fall and less likely to trigger an avalanche. It was all part of what David had been showing us in his pictures.

Once David learned that Scott was a web developer, he spent a good deal of time gathering advice from Scott about his Glacier Works website and the technology that the website was, or should be, using. It turned out that David was actually already working with one of Scott’s web developer friends back in Boston and that we were all three from Boston– small world…. Finally, he thanked us for coming, particularly because “trekkers don’t always feel welcomed into EBC by the ‘real’ hikers of Everest,” as he said, and he was glad we had ventured this “deep”.

Only when we were back in the safe, cozy confines of our hotel in Kathmandu 3 days later would we learn who this “David” guy really was. After looking up Glacier Works on the internet, we learned that this man, David Breashears, was kind of a big deal. He was a famous mountaineer and filmmaker who was the first American to summit Everest twice, had won 4 Emmy awards for his filmwork on mountaineering, and was the first person to transmit live footage from the summit of Everest in 1983. He had summited Everest FIVE times and co-directed and photographed the IMAX movie “Everest”, which we had just watched in Namche Bazaar before our push to EBC. I only wish I had known these details when we were standing there talking to him (he hadn’t even hinted that he had climbed Mt. Everest before, much less five times) … I would have had so many questions for him.

We retraced our steps through the meandering, rocky maze of EBC and found the clearing that marked its beginning edge.

We took one long last look at EBC (it’s a rather funny feeling when you look at a place and know that you will likely never see it again–), turned around, and literally began walking towards home.

That night we collapsed (and slept very well) at our lodge in Gorak Shep, a safe 2.5-hour walk away from the rumbles and crashes of EBC.

—–

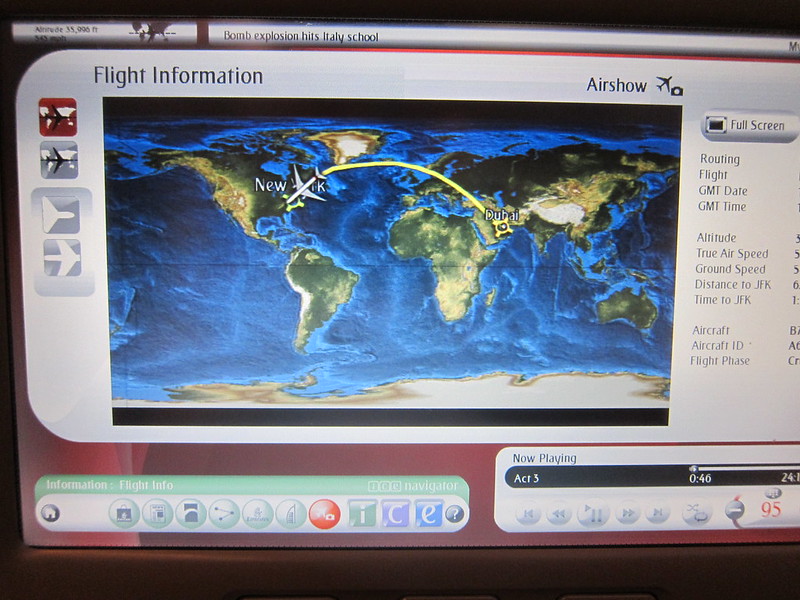

Leaving EBC marked the beginning of our return home from Asia, a symbolic end to our 8-month journey. Whereas the trip had felt like one long continuum of time and experiences until this point, turning from EBC marked the true start of our journey home– to Gorak Shep, and on to Lukla, to Kathmandu, and finally, of all places, JFK airport in New York. We didn’t yet have a place to call home (the road had been our home)… so JFK would have to do for now.